From above, the world is Eden. Fence rows stretch straight as Ishmael’s arrows. Corn and bean fields stitch a Jacob’s Ladder quilt. A cloud of dust fine as what God molded into man rises behind a horse and buggy traversing a dirt road.

As I bank the Curtiss over Horace Garrison’s farm, horses trot across a sun-baked field, disturbed by the roar of my engine. My hands squeeze the yoke as anger ruffles my feathers. My neighbor calls me boy to my face and worse behind my back, and lets his dogs chase Iris when she’s picking blackberries at the edge of our property. I suck in the hot wind caressing my face and focus on cottony clouds drifting above me. Up here I’m blessed with a view second only to God’s, and no man can take that from me.

As I approach our farm, Iris watches me from the shade of our ramshackle barn, a tiny figure in brown overalls. Since her mother died, she’s been my compass through long years in the darkness of my soul.

I descend and the ground rushes under me. The airplane’s fragile wheels are about to touch the ground when Iris steps into the sun with a woman I’ve never seen before. I lose concentration as my eyes linger on this stranger who seems so out of place on our isolated scrap of land. Forcing my attention back to the field, I’ve come in too fast and yank the yoke, tilting the biplane skyward. When I come around again, Iris has moved her hand to her heart.

The Curtiss returns to earth with a jolt strong enough to rattle my teeth. I take my boot off the throttle and roll to a stop. Iris and the visitor cross the field toward me. She’s half a head shorter than my daughter, who’s thirteen and tall for her age. The stranger’s skin is a pale cinnamon-rose and her light brown hair hangs long and loose, not in a bob like the ladies fancy these days. Her white dress clings to narrow hips. It’s hard to gauge her age or her people. She might be just shy of thirty and part Indian, or maybe not.

I climb out of the pilot’s perch, peel off my goggles, and wipe the sweat from my brow with a handkerchief. I don’t talk much to women, except the church ladies with their prim and proper ways, and my heart beats faster than a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs.

Iris gives me a hug and turns to the stranger. “This is Miss Martha. She’s come to see you.”

I pull off my cap and nod but Martha’s deep, dark eyes make my mouth dry as dust. Iris jumps into the silence. “This is my papa, Ambrose Root.”

“You can fly.” Martha’s voice is a warm, lilting updraft.

Folks gape when they see a colored man defy gravity, but Martha’s casual tone makes my feat seem as common as dandelions. I glance at the Curtiss, my sweetheart. “Mr. Crenshaw, the man I bought her from, taught me.”

“You bought it from his widow,” Iris jabs.

I flash her a sharp reprove. Mr. Crenshaw was a rich white man. I’m mechanically inclined and he hired me to help take care of the Curtiss and a Wright he bought out east. When he crashed the Wright into a tree and broke his neck, his widow sold me the Curtiss for a song. She couldn’t stand the sight of it.

Iris never forgave her.

Martha steps up to the machine and strokes a delicate balloon-cloth-and-bamboo wing. She closes her eyes and her face softens as if she and the machine are having a pleasant conversation. “What’s her name?”

I scratch my head. “I don’t recall that Mr. Crenshaw ever named her.”

“Don’t even think about naming her after me,” Iris snaps.

Martha turns back to me and smooths her dress with a delicate hand. “Flying is the closest we’ll get to heaven.”

I smile awkward-like because that’s exactly how I feel.

“I want to fly with you,” Martha says.

I open my mouth to tell her how flying is dangerous and not for ladies. But before I can speak, Iris steps forward. “My papa charges two silver dollars for a ride.”

I take in Iris’s smug face. When I bought the airplane, I told her I was going to make money giving rides, but even my own daughter won’t venture up in the air with me. “I don’t have money.” Martha’s eyes meet mine with no hint of embarrassment.

Martha’s like no woman I’ve met. There’s a strange and alluring beauty to her that causes my heart to stray from its usual rhythm and my common sense to fly the coop. “I was thinking of taking her up one more time before I put her to bed.”

Iris snorts. “Who’s your next of kin, case I have to notify them?” she says to Martha.

“I’m all alone in the world.” Martha voice is finely etched with melancholy. A lump the size of a Spitzenburg apple catches in my throat. I turn my attention to the clouds drifting across a sharp July sun.

“Being up there makes you forget your troubles.”

“That’s why I’m here.”

I fetch an extra pair of goggles from the barn while my mind searches for words of comfort I can offer her. But I sense that, like me, the vault of heaven is her consolation. When I step outside again, Martha and Iris are talking low. I pause for a moment. Martha’s a wisp of a woman, nothing like my late Elizabeth, but I want to take her slender hand and get lost kissing her lips the color of ripe acorns.

“I can’t stand here all day.” Iris’s voice snaps me out of my daydream. Her hands are on her hips and she’s got a look in her eye that could scare an old hound dog. I don’t blame her for hating the Curtiss. If anything happened to me, she’d likely end up in the colored orphanage, even though she’s smart and tough enough to run the farm on her own.

I hold out the goggles to Martha but she shakes her head. “I don’t need them.”

“Lot of wind up there.”

“I know.” Her lips turn up slightly, as if I was explaining that air’s for breathing. I slip the glasses into my overall pocket. The three of us turn the plane around so it faces westward toward the sun. I climb into the pilot’s seat and offer my rough paw to help Martha up to the passenger chair beside me. Her delicate fingers remind me of the spiderweb of control wires that stretch across the fuselage and wings.

“I’ve got ham hocks simmering so you best not be long,” Iris calls to me.

I flash her a grin and check the aileron, the stabilizer trim, and the canard. Iris slips on a pair of ragged work gloves and walks slowly to the machine’s tail. She stands behind the pusher and turns the propeller slowly clockwise.

“Propped,” Iris calls out.

“Contact!” I reply.

The airplane shakes as she gives the propeller a hard yank, once, twice, until the engine roars to life. She hurries out of the way.

I blow her a kiss and press my boot to the throttle. As we bounce across the dirt, Martha’s hair blows wild and she pushes it from her face. We pick up speed and I pull back on the yoke. The ride immediately smooths as we take flight.

The first time Mr. Crenshaw took off with me in the passenger seat, I prayed I wouldn’t lose my lunch. But as we gain altitude and land recedes, Martha’s face is calm, like we were taking a slow buggy ride.

“How you doing?” I shout to Martha over the engine’s roar.

She cocks her head and gazes at me sideways. My heart swells bigger than a hot air balloon at her gentle smile. “Thank you,” she replies.

We soar above the trees bordering my land. A flock of starlings floats on the wind to our right. Martha watches them, her face awash in longing. I’m looking at her with the same desire. I nod toward the birds. “I wonder what they think, seeing us up here?”

“That you don’t belong.”

I’m used to white folks judging a colored man with property and a good name. But I sense no rancor in Martha’s tone. I want to learn more about where she comes from and why she’s here. When we land, I’ll invite her to supper so Iris and me can get to know her better.

A prickle of worry tickles the back of my neck to remind me I’m probably running low on fuel. I should turn back but I let this moment linger. I’m in no hurry to be anywhere but with this woman.

Common sense finally prevails and I lean right to bank back to our farm. The weathered barn appears. Iris has returned to its shade. The Curtiss flirts with the ground before we touch Earth again. I jump out and offer Martha my hand. Our eyes meet as she steps to the earth. I open my mouth to extend a supper invitation but my words float away before I can catch them.

“You going to stand there till midnight or help me roll your contraption into the barn?” Iris says as she strides toward us.

“Sorry,” I say to Martha. “I’ll be right back.”

She smiles demurely, and I hurry to one of the airplane’s wings. Iris pushes from the other side and together we roll the machine into its nest.

“I’m going to invite Miss Martha to supper,” I tell Iris.

She frowns but says nothing. I step back outside. The sun is settling toward the horizon. My eyes sweep the field and farmyard.

Martha is gone.

###

Iris places a bowl in front of me. I’ve got no appetite and listlessly stir the thick soup with my spoon.

“She was a strange one,” Iris says as she settles across from me. Her dark, intelligent eyes remind me of her mother.

I wrinkle my brow as my mind circles. “Where did she disappear to? It’s five miles to town and she didn’t have a horse or conveyance.”

Iris balances ham and beans on her spoon. “It’s just as well she’s gone.”

“What’s got your knickers in a twist?” I ask, though I already know. Iris was six when her mama died. Elizabeth was practically a ghost by the end, swallowed by our big feather bed. It’s been just me and her since, and we’ve both gotten used to it.

Iris takes her time chewing before she answers. “There’s a sadness about Martha, like she’s carrying the weight of the heavens on her shoulders.”

I reach across our rough oak table and take Iris’s hand. “Maybe she’s lost someone like we did.”

Iris focuses on her supper. “I just don’t want you to get hurt. You’ve been through enough pain.”

I break off a chunk of crusty bread from the loaf between us. She rarely speaks of it, but I know the same sorrow lies deep in Iris’s heart. “Pain is a part of living. The good Lord requires us to persevere.”

###

I don’t want to hold onto a hope that might never manifest so I bury myself in farm work and tinker with the Curtiss’ engine. But my mind is continually pulled to Martha’s slim figure and dark eyes. I pause my work and look for her, not on the dirt road that fronts our farm, but in the sapphire sky because that’s where she seemed most at home.

Two days later, a knock brings me to our front door. Martha’s face is indistinct through the screen and for a moment I believe she’s a beautiful dream.

“I’ve come for another flight,” she says when I open the door.

“I’ll get my hat and boots.” My feet seem to float over our hooked rug as I hurry to dress.

###

The next weeks passed in a fog of delight and misery. Martha appeared every few days, always in the same white dress. Her sweet smile encouraged me to fly higher and farther than I’d ever dared. The Curtiss is a temperamental lady and something’s as likely to break as not. Thankfully, Iris doesn’t know the risks I took. She grudgingly accepted Martha’s presence and her papa walking around in a sweet daze.

As we floated above the earth, Martha’s words were few and laced with sadness and loss. She spoke of the earth’s beauty and the joy of being untethered from it. I feared to press her with questions and break my bubble of contentment. Her presence was enough to release joy that had been shackled for too long.

###

But now I stand before the closed barn door, unable to bear even looking at my Curtiss. It’s been twenty-three days since I last cherished Martha’s company. I ride into town and ask guarded questions of Mr. Evers, the white grocer, and my friend Ollie who works in the stockroom at the five-and-dime. Nobody’s laid eyes on her. When I return home, I sit on the front porch whittling a stick as my mind chews on the mystery of Martha.

Iris cooks our meals and tends to the house and the chickens. She encourages me to take the Curtiss up, even offering to join me. Worry creases her brow when I shake my head. I know she’s thinking I’m lost in that shadowed land again because I fear the same.

###

One morning a few days shy of September I lead our old mare Gwen into the barn and am startled to find Martha standing next to the Curtiss, her perfect features alight in the gloom. “Martha!” I rush forward to embrace her but stop short. She’s thinner and paler, and her eyes have lost some of their intensity.

She steps into the narrow slit of sunlight streaming into the barn and my heart takes flight. Gwen dips her head to accept Martha’s touch and I wish I was a horse. “I don’t have much time.” Her words are barely a whisper.

Fear courses through me. “Are you ill? There’s a colored doctor in town. You don’t have to worry about the money.”

Her eyes are fixed on the Curtiss and I’m not sure if she even heard me. “I want to fly your machine.”

I shake my head. ”Flying an airplane isn’t for a lady or for anyone who ain’t a bit crazy.” Her face is set. “I was born to fly, not you, Ambrose Root. I want to take you somewhere.”

I scratch my head. For the first time, I fear she might be off her trolley. “You know I’ll take you anywhere.”

“You’ve given me something I thought I would never experience again. Please do this one last thing for me.”

I gaze at the dust-covered floor, unable to refuse this woman. Her fingers flit across the back of my hand. “Trust me.”

My heart lurches like a slipped gear. “Just tell me what’s wrong.”

Her eyes flash with dark intensity. “We used to be innumerable, turning the sky storm black. But now I’m the last and I need to do this for the others who are already gone.” I don’t understand her words but the disconsolateness in her voice causes tears to flow down my cheeks. I haven’t cried since my Elizabeth died. At this moment, I’d stop the world on its axis for Martha.

Together we open the barn doors wide to embrace the glorious late summer morning and push the Curtiss into the sticky Ohio air. I don my goggles and Martha climbs into the pilot’s seat. I sit next to her and explain the throttle pedal, how the wheel controls pitch and yaw, and how to use the shoulder yoke to bank the airplane.

She nods and asks no questions. Fear hangs tight in my gut as I climb out and walk to the back of the plane. Falling in love is one thing, but dying with this woman who’s got me spellbound isn’t how I want this story to end. But deep in my heart, I trust Martha. It’s the same blind faith that allowed me to climb into the Curtiss the first time I flew with Mr. Crenshaw. Something so heavy shouldn’t defy the gravity that holds us to this plain. Flying made me believe in miracles and Martha is nothing short of one.

I turn the propeller a couple of revolutions then grip the blade above my head and rotate the prop until I feel compression. I reach up again to the highest blade as I shift my weight away from the arc of the prop.

Then I mutter a brief prayer.

“Propped!” I shout.

“Contact,” Martha calls back.

I pull down hard. The engine never starts on the first try but this time it roars to life immediately. The airplane rolls forward and I run around the wing to jump into my seat. Martha offers me a contented smile that makes my heart soar.

As the wheels lose contact with the ground, my fear falls away. Martha tilts the machine upward, banking smoothly so we’re heading east towards a hazy horizon. We sail over Garrison’s farm but I don’t give him a second thought. It’s been a long time since I was this happy, not since the day Iris was born.

Martha flies over farms and roads I don’t recognize. I’ve never taken the Curtiss this far from home and my palms are sticky with sweat. “We should turn around,” I say.

“We’re almost there.”

We cross a meandering stream and thick woods. A lush green pasture lies beyond them. Martha begins to descend. There’s no farm or house in sight, but I’m still nervous. “I don’t know if we should land here. We don’t know who this land belongs to.”

“No creature owns the land or the sky, Ambrose. You should know that.”

A red-and-white checked square jumps out against the bottle-green landscape. It’s a blanket spread in the middle of the field. A wicker basket waits at its center but there’s no picnickers nearby.

I grip the sides of my seat. Take-offs and landings are the most dangerous moments of piloting an airplane. “Take her in gently. Pull back on the wheel as you let off on the throttle.”

“I know, Ambrose.”

Martha sets the airplane down zephyr-like and I laugh with joy and relief. “I couldn’t have made a better landing myself.”

Martha gives me a sideways look with impenetrable eyes. “Let’s eat.”

She takes my hand and tingles of heat lightning shoot through my body. Birds sing their joy in the bordering woods. I scan the field for picnickers.

“You don’t need to be afraid,” Martha says.

I scratch my head in confusion. “But how’d the basket get here, and how do you get out to our farm for that matter? I’ve never seen any conveyance bring you. You just show up like an angel.”

She turns to me and touches my arm. “I can’t explain it, Ambrose. I’m surrounded by wire, but when I close my eyes, I can go anywhere I please.”

“But where do you come from, and who’s keeping you prisoner?”

She rises on tip-toes to press her lips to mine. Questions flee from my mind like flushed rabbits. Being with Martha is all that matters.

She lowers herself onto the blanket and stretches her bare legs across it. I sit opposite as she pulls three cloth sacks from the basket. Opening the first, she shakes shelled beechnuts into her hand. She pops the seeds in her mouth and swallows them without chewing, then holds her open palm out to me. I nibble on the seeds and she watches with amusement as I enjoy their oily texture.

The other sacks hold thistle and sorghum. I try my best not to gag as I chew and swallow. This is the strangest picnic I’ve ever attended, but I’d rather be here with Martha than eating pepperpot on Christmas Day.

“Martha, I don’t know who you are or where you come from, but I’m so blessed to have you here.”

She offers a melancholy smile. “I knew a man who could fly would understand me better than the others. I’m sorry we have such a short time together.”

I lean forward and grasp her hand. “If you’re sick, there’s got to be something I can do. Just tell me what ails you.”

“You can’t take away my pain, but you can do one more thing for me.”

My whole body courses with the desire to make things right for her. “Anything.”

Martha rises and turns her back to me, perching on two delicate bare feet. “Help me with these buttons, Ambrose. I’m not used to them.”

I stand but my legs almost give way. “Martha, we don’t need to hurry things. Let’s get to know one another. I’ve never even had you to supper.”

She turns again, her face set with determination. “It has to be now. There’s not much time left.”

I shake my head slowly. “I don’t understand.”

“You don’t need to.”

Despite my pounding heart and shaking fingers, I manage to release the long row of buttons. When I’m finished, she faces me and drops the dress from her shoulders without a hint of modesty. She is completely naked. My heart and body are overwhelmed with love and desire. Her voice is an intoxicating whisper. “Get undressed, Ambrose. I need you.”

I’m in a strange dream where thought ceases and only senses remain. I lay next to her and when we kiss, the distant birds hush. I bury my face in the soft curve of her neck and breathe in the scent of oak moss and mast. Something tickles my nose and I brush away a feather.

Afterward, we lay side-by-side on our backs, naked and unashamed. I close my eyes and a wood thrush’s melodious song rises from the woods. I’m shrouded in a wave of peace that I’ve only felt while airborne.

I must have drifted off to sleep because when I awake, the birdsong has ceased and the breeze has picked up, rustling the leaves. I reach for Martha but find only empty space. The surrounding meadow is empty. Only Martha’s white dress remains, a ghostly vestige draped across the blanket.

Iris doesn’t appear when I land the airplane back at our farm. I find her at the kitchen table, an untouched cup of coffee in front of her. I can’t explain to her what happened. I’m not sure myself. Instead of my heart rejoicing at the memory of our passion, it beats with a slow, mournful rhythm.

###

Each morning I perform the same evocation, rising early, pulling on my overalls, and walking out to wait in the middle of the field. I gaze up at the dawn-kissed sky, waiting for Martha’s return, but I sense the hopelessness of my yearning. Something precious has been sucked out through a hole in the world, and what has vanished can never be replaced.

Ten days after I last saw Martha, Iris hitches Gwen to the wagon and rides into town for supplies. She returns late afternoon, her market basket on the seat beside her. A newspaper pokes out from between dried goods. She always brings one back to catch up on the outside world.

Iris climbs out of the wagon, brushes the dust from her skirt, and lifts the basket from the seat. I stand on the front porch but she doesn’t acknowledge me, as if her mind is far away. A bile of vague fear rises in my gut. My voice shakes as I ask, “Anything new in town?”

Iris doesn’t speak as she passes me the newspaper. I unroll it and stare at the front page.

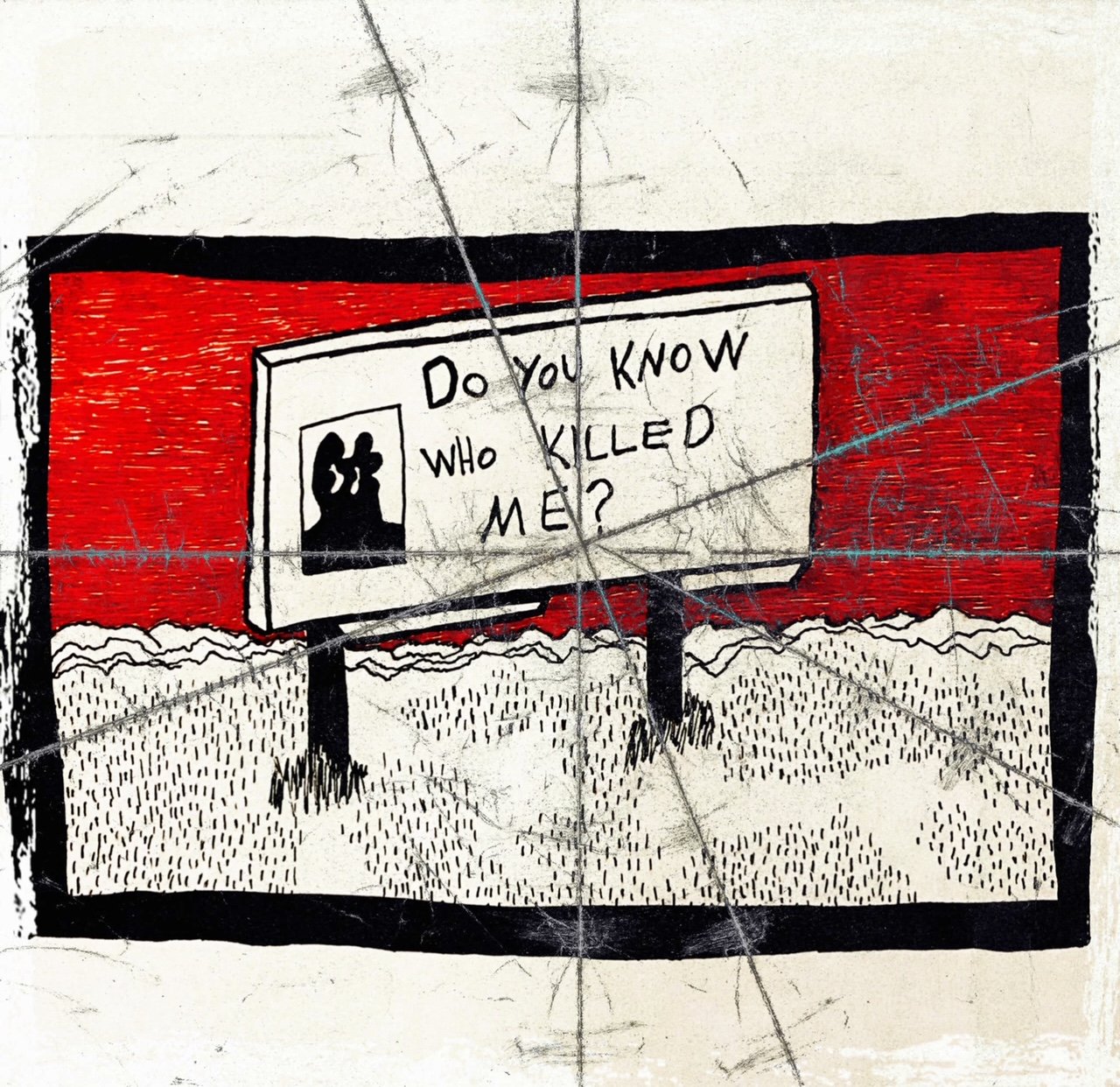

Last Passenger Pigeon Dies

CINCINNATI, Sept. 2. – Martha, the last passenger pigeon, died yesterday at the Cincinnati Zoo. She was 29 years old. The zoo had offered a $1,000 prize to anyone who could find a male to preserve the species. The carcass will be shipped to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

The North American passenger pigeon was once ubiquitous in our skies, with flocks of thousands being observed overhead. They were slaughtered with ruthless thoughtlessness until they diminished and disappeared from our world.

The newspaper slips from my hand. A breeze kicks up and scatters the pages across the dreary landscape. Neither of us attempts to chase them down. I collapse into the front porch rocker and don’t stir for a long time.

The sky is the color of a ripe apricot when I finally rise and stumble toward the barn, my mind intent on what I must do. I yank the door open and the sunset illuminates the Curtiss waiting patiently for me. I grasp the axe hanging from a hook on the barn wall. Only a few weeks ago, I sharpened it on my whetstone until the bit could split a blade of grass. I grasp it by its throat and approach my former love. I only wish I could destroy all the airplanes in this world because no man deserves to fly.

As I raise the axe, my eyes are drawn to a small object in the pilot’s seat, wrapped in burlap. I drop the weapon and gingerly lift the bundle. My breathing ceases as I unwrap a pure white, elongated egg.

I sense Iris standing behind me. Her eyes widen at the treasure cupped in my outstretched hands.

“One of the hen’s gone broody,” she says as she takes the egg. “I can slip it under her and we’ll see what hatches.”